A more professional approach to managing our public wealth could yield several percent of GDP in annual non-tax revenues.

Just as businesses and households assess their balance sheets before making investment decisions, so should governments.

When budgets become imbalanced, the most effective way to boost revenue is by improving the management of assets and liabilities.

Today’s fiscal threats call for a fundamental transformation of public finance management.

Traditionally governments have focused exclusively on increasing debt and raising taxes, overlooking the full scope of their assets and liabilities. This narrow approach has deprived policymakers of crucial insights and accountability, and has led to inefficient resource allocation and potential inequities within and across generations.

It doesn’t have to be this way. If governments introduced accrual accounting-driven targets and adopted public-sector net worth as a key metric of fiscal health, they could generate new revenue streams and strengthen their fiscal positions without cutting essential public services or resorting to tax hikes.

A more professional approach to managing our public wealth - assets - could yield several percent of GDP in yearly non-tax revenues.

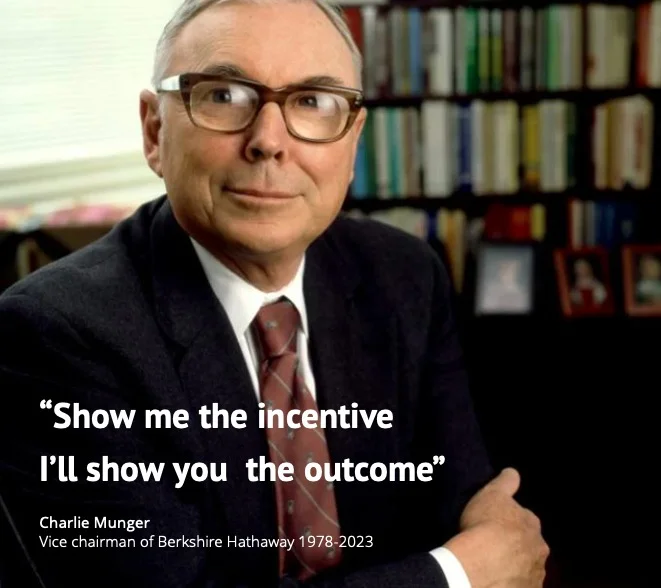

“Its not rocket science, it is done in the private sector every day.”

Just as a company or a household would look at their balance sheet when making investment decisions, so should a government.

In fact, the government is the biggest wealth manager in any country and at every level of government.

“It sounds like a free lunch, and it pretty much is”

To strengthen public finances, we should of course always look at

Better asset and liability management can significantly increase non-tax revenues—by several percent of GDP per annum.

So, what do we mean when we talk about government assets and how much value is hidden in the balance sheet? Total amount of assets in any government is probably worth around 3 times GDP of that country, state or city.

Half is infrastructure and the other half is commercial assets.

Public Commercial Assets consists of real estate and operational assets . Real estate assets are worth the equivalent of one times GDP and operational asset perhaps about half of GDP.

Operational asset are government owned business of all kinds;

If we can accept that governments – like other organisations – should manage their finances in relation to Net Worth – Public Net Worth – not Net Debt, and should be willing to invest to meet future needs, then we unlock the potential for professional management of our public assets.

This could make a major contribution to meeting the fiscal challenges of the coming decades.

Professional management requires a separate management vehicle to manage the assets, at arms-length from short-term political influence. This vehicle should be an independent holding company that we call a Public Wealth Fund (PWF). This type of fund exist to manage existing public commercial assets – frequently property or operational assets – in a way that will maximise financial value to the taxpayer.

It is akin to a ‘sovereign wealth fund’ and expression that cover a wide range of government-funded investment activity. The classical sovereign wealth fund ‘SWF’ exists to invest public funds in a diversified portfolio of investment assets to meet future needs.

This requires that we manage these public commercial asset as if they are privately owned, including allowing for competition – that is deregulation of these sectors and take out any kind of subsidies given through these assets. Instead provide subsides or economic

support directly to the individuals that needed instead of going through any public commercial assets or operations.

When it comes to operations with a universal service obligation, it requires that we separate the non-commercial parts from the commercial and provide a subsidy to the non-commercial through a competitive process to a wider number of providers than the government-owned entity.

Just like any privately owned commercial operation or real estate asset, the purpose of owning these assets is to maximise value or public net worth, and thereby creating fiscal space and debt sustainability.

Governments around the world insist that private sector organisations, and many public sector ones, produce regular, timely, comprehensive financial accounts. The larger, more complex the organisation, the more demanding the accounting requirements. Accounting is all-pervasive; management information systems provide the information on a day-to-day basis that is aggregated into formal financial accounts. Everyday actions are driven by, and aligned with, the basis on which the organisation’s financial performance is judged.

However, with the exception of New Zealand, governments generally do not hold themselves to the accounting requirements that they impose on others, and neither do they use a comprehensive set of accounting information as the basis for decision-making. Instead, most governments rely on cash-flow and debt-based fiscal targets or rules.

These comprise an in-year target or rule related to whether revenues are meeting expenditures, together with a target for total government borrowing. Both are usually expressed as a percentage of GDP. Seen through an accounting lens, these rules are deeply flawed, for two reasons.

First, they ignore most of the balance sheet. On the liability side of the balance sheet, only debt liabilities are taken into account. Non-debt liabilities such as public sector pension obligations are ignored. In some countries these could be even larger than total government debt, the UK has been an example of this. Not to measure or control these seems like a very strange omission.

On the asset side, debt-based targets pay no attention to whether borrowing is used to fund long-term investment or near-term consumption. This is not to say that the Government does not measure this – it does. But the debt target always dominates. As a result, the purchase of an asset which would deliver public benefits (financial or otherwise) for decades to come is treated in the same way as spending on current services that benefit only today’s recipients.

This can only distort decision-making and penalise investment. Moreover, there are strong reasons to believe that the value of government assets – especially property assets – is severely understated on government balance sheets, where they exist.

Second, debt-based targets tell us very little about intergenerational fairness. As we have seen, if we only measure debt we pay no attention to whether the proceeds of debt issuance have been used to invest for the future, or simply to meet current needs.

Neither do we know whether other liabilities are being stored up for the future. The basic output of a company’s – or government’s – accounts is an assessment of Net Worth, which, as I do not need to tell you, is the difference between total assets and total liabilities. If the accounting is done well, Net Worth therefore addresses both of the problems highlighted above, and allows regular assessments of the legacy that each cohort of taxpayers are leaving to their successors.

Not only does assessing government finances based on Net Worth make sense analytically, it also allows governments to act like other organisations and borrow to invest, and provides incentives throughout government for decision-makers to take into account, and manage, the value of the assets that they use and the liabilities that they incur in delivering government services. This is essential if governments are to take advantage of the opportunities which wealth funds can offer.

Despite the lack of good accounting for government property values, it is not difficult to derive a working estimate for actual or potential value that can provide a sound basis for developing a PWF strategy. Modern online mapping technology, used in combination with the data from the Land Registry or other public sources, allows usable working data for any given urban area to be generated in a few weeks, and at very modest cost. Lack of data is not an excuse for a failure to examine this valuable opportunity.

A more professional approach to managing our public assets could yield several percent of GDP in non-tax revenues. A fiscal space that is badly need in many countries to meet the future needs of society as a whole.